Have you ever glimpsed a long-tailed weasel, Virginia rail or 13-point black-tailed deer buck roaming in Tigard?

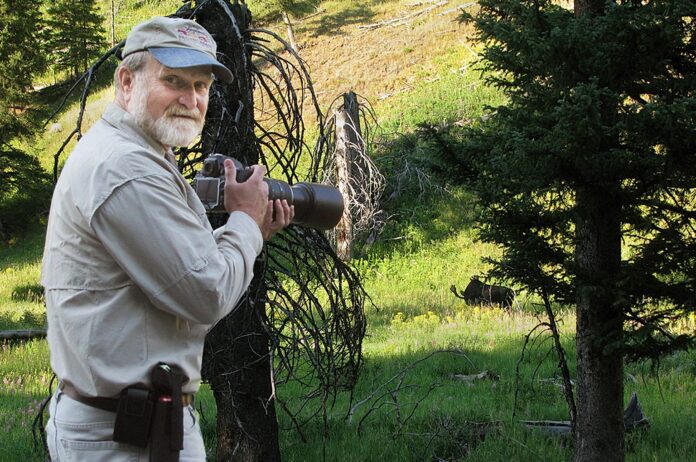

Wildlife photographer Steve Conner has. Camera in hand, the Tigard resident hunts for chances to capture images of such creatures often furtively frequenting local parks, wetlands and even neighborhoods.

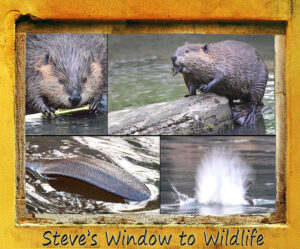

His other local quarries have included heron-variant masters of disguise called bitterns; crazy-blue-colored lazuli buntings; and acorn woodpeckers, bald eagles, beavers, great-horned owls, kingfishers, muskrats and nutria.

The 75-year-old Conner retired six years ago from a career doing various stripes of high-precision photography, including a period photographing underground environments for the U.S. Bureau of Mines. Now, retirement has let him augment a pursuit of nature that he began as a boy. About three times a week, Conner grabs his Nikon D800 camera and blend-with-background clothing to explore parks and reserves, especially those in Tigard and Tualatin.

Conner traces his wildlife photography to serene early mornings when his father took him on rounds to maintain 28 family beehives in the countryside around their Kansas home. At dawn, they brought lawn chairs and hot coffee to watch, listen and feel nature wake up, he says.

Since then, he recalls many instances when his senses were so attuned to his natural surroundings that the slightest breeze, motion or rustle drew his attention. On one dark evening outing into protected lands along the Imnaha River in Oregon’s northeast corner, he remembers settling on a perch and zeroing in on the minutest sounds. When a single snowflake spiraled downwards and alit on his knee, he had the sense of feeling, hearing and seeing the landing.

Like bird watchers, wildlife photographers most avidly hunt shots of species or sights they understand to be available to them in particular locales but have yet to capture them. This year, Conner made many trips to Oregon’s Cannon Beach to photograph an elk on the beach without people in the background. He’s had no luck so far – but he keeps on trying.

These days, Conner typically makes his outdoor excursions with his wife, Connie, who also shoots photos. Like anglers and hunters, they most often go out mornings or evenings. “You see most nature early and late,” Conner said. By contrast, they try not to disrupt their prey.

Favorite local haunts of the Conners — who here relocated 25 years ago from Spokane, Wash. — include Englewood Park, Summer Lake Park and Derry Dell Pond in Tigard, Tualatin River National Wildlife Refuge near Tualatin and Tualatin Hills Nature Park in Beaverton. Within the region, they also venture further afield to Sauvie Island Wildlife Area in Portland, Baskett Slough National Wildlife Refuge northwest of Salem and Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge in Washington state.

For other aspiring photography hobbyists, Conner has offered classes titled “Expanding Your Ability to See” and “Wildlife Photography” at West Linn Adult Community Center.

As to the three examples of his target species in Tigard or Tualatin, he:

Once glimpsed a long-tailed weasel but has yet to photograph one.

Has photographed secretive Virginia rails, more often found by way of their staccato call than their appearance around the size of a robin but more elongated.

Has captured images of a deer buck with six points on one antler and seven on the other, but he has yet to see the deer after its antler velvet has shed.

In Conner’s passion to photograph nature, the goal always stays the same: to pursue, document and share images of wildlife. He shows them to friends. He puts his favorites in rotation on his smart TV.

“I’m not trying to make a living on them,” Conner said. “I’m just enjoying them.”

Steve’s Wildlife Photography Tips:

The key to nature photography is presenting the mildest possible sensory presence to wildlife, Tigard photographer Steve Conner said.

“To them, you are a predator, regardless of whether you have a gun,” he said.

To get close enough to capture the best images of coveted species, the first step is researching their sensory makeup – their strengths, weaknesses and sensitivities. Successful photographers learn their subjects’ sense of:

- Smell. Fragrances, deodorants and body, hair or laundry soaps can register as foreign — and dangerous. Minimizing artificial scents helps avoid alarming animals.

- Sight. Some species have remarkably sharp vision. For them, it makes sense to wear green, khaki or camouflage clothing to blend into the backdrop.

- Sound. Many animals have keen hearing. When that’s the case, it’s wise to set up well before the optimal light arrives — and keep noise to a minimum.

Bottom line: The best nature photographers study the sensory profiles of the species they pursue.