Ninety-seven years ago, Golda Fabian was born to a logger and his wife who lived in Grand Ronde, but she was no small-town girl and had an adventurous spirit. She was ahead of her time, joining the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II and fighting discrimination against women in the military and throughout her career.

“My mother had two children with her first husband when he died in the flu epidemic of 1918,” Golda said. “She met my dad at a pie social where the women bid on pies made by the men without knowing who baked them. I’m sure my dad’s mother baked his pie. My mother bid $1 for my dad’s pie, and they ate it together. He asked her to dance. It was love at first sight.”

Golda, one of five children, had polio when she was 2 years old, and when she was 11, she spent three months at the Shriners’ hospital in Portland to have corrective surgery on her right leg. Years later, a military doctor conducting a boot camp physical exam said she could not remain in the Marine Corps because one foot and leg were a little smaller from the polio although she had passed the entrance physical exam.

“He told me to wait for my discharge orders, and I started crying,” Golda said. “He sent me to the chaplain, who told me, ‘There’s a war on.’ I kept doing my drills and classes and never heard any more about it.”

Around the time she was being treated for polio, “my parents decided the logging profession was too dangerous for my dad to continue working in,” Golda said. “He lost a hand in an accident before they were married and had a hook to replace it. We moved to Sheridan, and when I was in the seventh grade, we moved to Cloverdale.”

Golda graduated from high school in 1941 and moved to Seattle where her aunt had a good-paying job operating a “comptometer,” which was an advanced adding machine. Golda went to night school, earned her certification and got a job at Boeing in the payroll department.

“I had gone as far as I could at work, and I was always kind of adventurous,” Golda said. “I felt I wasn’t doing enough to help the war effort in my job… and I have always loved uniforms. Since I have always been competitive, if I was going in the service, I wanted to go into the one that had the highest requirements and was the most difficult to get into.”

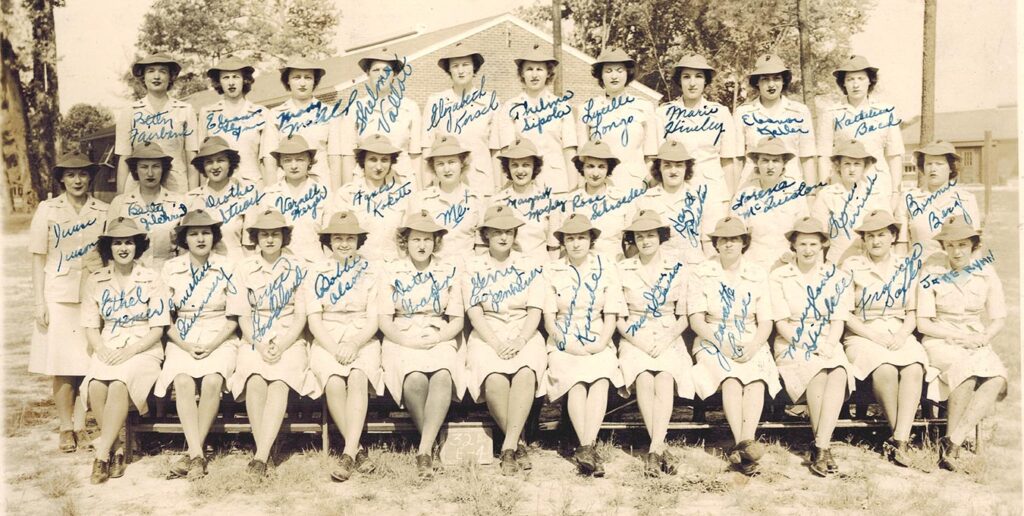

Golda enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps on March 2, 1944, and left for boot camp at Camp Lejeune, N.C., on April 28, 1944, where she quickly learned the men did not want to deal with “petticoat Marines.”

While the training was not nearly as rigorous as the regimen today, “it was pretty formidable,” Golda said. “The first week I thought I was going to die, and the second week I was hoping I would.”

In addition to classes, there was close order drill and physical endurance training, and Golda added, “The gas chamber drill was the worst experience, and all of us remember that one vividly.”

After boot camp, Golda was assigned to two weeks of mess duty, cleaning trays and the mess hall from morning to night while enduring high temperatures and humidity.

Next she was assigned to the Marine base in San Diego and went to the Sound Motion Picture Technicians School at the adjacent Navy base. “When we had completed the course, the officer in charge told us that we were all competent enough to work in any theater in the U.S. except, he added, ‘You women would never be hired because it is considered a man’s job.’”

There were no openings in theater, so Golda was assigned to the post office at the Marines Air Depot at Miramar, Calif.

“I was assigned to the directory service in the base post office, which is where I worked until I was discharged,” she said. “The base was the processing point for all Marine Corps air personnel going to the South Pacific and coming back to the states for reassignment. Consequently, there was a constant flow of mail going both ways, which had to be readdressed to each recipient.”

The off-duty hours were filled with fun activities, and San Diego was 16 miles from Miramar, “where the town seemed to be populated mainly by Marines, sailors and soldiers with the civilians just there to take care of their needs such as food and entertainment,” Golda said. “When on the base, in our leisure hours we attended the base theater or went to the ‘slop shop’ where they served beer and sodas, and there was juke box music to dance to.”

In July 1945 Golda was swimming in the base pool and broke her right arm while diving from the 3-meter board. Although she was officially in the sick bay until the war ended, she was assigned the duty of cleaning the women’s rest rooms after a Navy nurse told her, “You’ve got a good left arm so you are in charge of the head.”

Golda added, “When I wasn’t polishing mirrors and cleaning toilets, they gave me capsules to fill with a medical powder and bandages to roll.”

Out of the sick bay, Golda had some leave time and went to Georgia to visit a 1st Division Marine she had met and developed a relationship with although they were never on the same coast at the same time after the initial meeting. “Everyone wrote letters because it was so hard to make a phone call with one phone for 500 women,” she said.

“I just planned to visit Georgia for two weeks, but after one week I was married and after two weeks I was pregnant. The following week I reported back to Miramar and put in for a discharge. I had been promoted to PFC on Sept. 13, 1945, and my pay at the time of my discharge was $54 a month. I received my honorable discharge on Nov. 23, 1945, and after a brief visit home to Oregon and Washington, I returned to my husband in Georgia.”

Unfortunately, her marriage didn’t have a happy ending. Her husband suffered from what is now known as PTSD from his war experiences, and he became an alcoholic. They had three children, and Golda went to the University of Miami to major in accounting. She was the only woman in the program and discriminated against by the professor until the men in the class stood up for her.

“I left my husband after 11 years of marriage, and I was 12 credits short of a degree because my GI Bill funding expired,” Golda said. “With three children to support, I couldn’t afford to finish.”

Back in Oregon, she met a man originally from Hungary, and after going together for several years, Golda married Andy Fabian, who had two daughters.

“We were married for 33 years,” she said. “We went to Hungary nine times and visited other parts of Europe.”

Andy died 12 years ago, and Golda has stayed busy, including being active in the Women Marines Association. Remembering her time in the service, she said, “It was one of the best times of my life, and the pride I felt in wearing the Marine Corps uniform is indescribable.”

Last October Golda moved from her house in Tigard into King City Senior Village.