Tigard-Tualatin students returned from the holiday break with a new violence policy in place, and an accompanying consequence “matrix” slated for roll-out later this month will spell out circumstanced-based repercussions, but some in the community remain impatient with the pace of change and unsatisfied with the process.

School board members unanimously approved the Student Acts of Physical Aggression or Violence policy during a December 11 meeting where emotions ran high.

The two-page document – which covers reporting, investigation, district accountability, and discipline – unequivocally denounces school violence and defines prohibited acts, saying the board “will not tolerate student acts of aggression or violence.”

But it’s the second piece, a consequence matrix, shaped over a series of community roundtables and board work sessions in October, that lays out a clear set of tiered responses to various infractions.

“That (community collaboration is) what it takes to deal with these situations with integrity and wisdom,” said parent Brad Dorsey, who participated in the roundtables and policy creation.

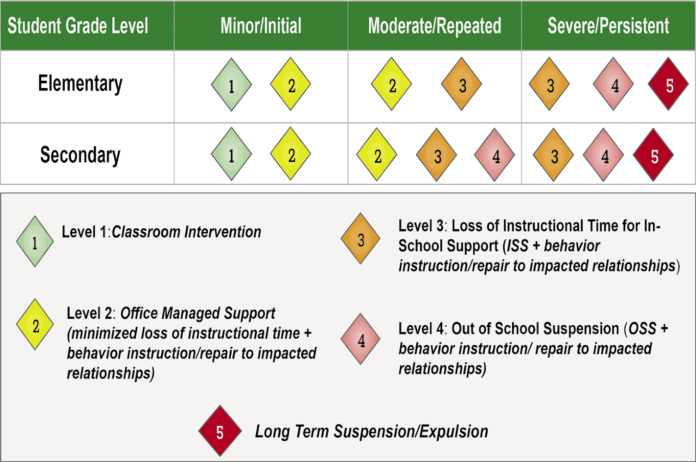

The guidelines are rooted in restorative justice practices aimed at creating healing for all parties. It’s a multi-tiered discipline structure that factors students’ age and past behaviors, among other things, to determine “clear, thoughtful consequences,” School Board Chair Tristan Irvin said.

Suspensions and expulsions are not off the table, but with a few exceptions, they aren’t an auto-response.

Variables like whether it is a first or fourth infraction are used to create a menu of steps that teachers and administrators should take in response to everything from academic dishonesty and excessive tardiness to vaping, hazing, bullying, aggression, threats, and assault.

In younger grades, the matrix leans heavier on containing the process within the classroom.

The new policy is part of a forthcoming update to the district’s student rights and responsibility handbook. It tackles issues that have emerged with technology, like recording and sharing violent incidents, and disruptive behaviors that increased in schools statewide after students returned from pandemic closures.

“There hasn’t been a (specific violence) policy because the climate hasn’t warranted one,” said Irvin, likening the addition to weapons policies implemented in response to the national surge in school shootings.

Work on the policy was already underway in late September when an unprovoked assault at Hazelbrook Middle School cast a national spotlight on Tualatin and accelerated the conversation.

The video of a student grabbing a classmate’s backpack from behind, pulling her to the ground, and dragging her by the hair in the crowded hallway as students were leaving school went viral on social media platforms, gaining more than a million views. It was followed by threats that led administrators to close Hazelbook for two days.

For some, the changes can’t come fast enough.

“I can no longer provide a safe teaching space under current conditions due to escalating student behaviors, verbal abuse, and violence,” Ronnie Profit, a third-grade teacher at Durham Elementary, told the school board.

She and a handful of other teachers, parents, and students aired frustrations with a system they say has too long left bad behavior unchecked, and, in some cases, rewarded.

“Disruptive behavior makes it hard to focus,” one 7th-grade student said. “It feels like the students who are disruptive just come right back to school and get treats to bribe them to be good.”

The struggles aren’t unique to TTSD.

“The challenges in school districts are real, and this is unprecedented territory coming out of the pandemic,” Dorsey said.

The nonprofit media outlet Education Week concurs. In 2022, EW reported a nationwide rise in violence and school shootings?) after students returned to the classroom from COVID-19 shutdowns.

Despite the parallel stories of increasingly untenable school environments nationwide, some in the local community place the blame on Superintendent Dr. Sue Rieke-Smith.

In December, the parent group Tigard-Tualatin School Alliance for Safety and Education began circulating a petition calling for her ouster. Its website also links to the results of a teacher survey and a section of stories shared by teachers, students, and parents.

“There are a considerable amount of students who are safe but do not behave respectfully towards teachers and other students,” one teacher anonymously wrote. “Their disruptions constitute a significant loss of learning and teaching time. I feel that students are not being held accountable for their actions in a way that results in the behaviors discontinuing. I fear we are not helping them prepare for adulthood and a society that holds them accountable by much harsher consequences.”

The school board has yet to receive a recall petition, and it’s unknown how many people have signed or if they are all verified Tigard or Tualatin residents.

Teagan Milera, who has two kids in the schools, said she considers behavior problems “a top-down issue.”

Milera was part of a volunteer crew assembled this fall to help monitor Hazelbrook’s cafeteria and hallways during lunch, pick-up, and drop-off times. The program was a trial run as the schools explored ways to incorporate volunteer parent help in middle and high schools.

“I really feel like the board and Dr. Sue are hiding behind this equity-and-inclusion stance to the point that it makes no sense,” she said. “There have to be extremely clear expectations if those consequences are not met.”

Parent Victoria King, who’s part of the recall effort and, like Milera, volunteered at Hazelbrook last month, points to what she sees as a failure to follow through.

“What we have seen from this administration is a lack of policy implementation, so I really don’t anticipate (the new system creating) change,” she said.

But others, like Dorsey and Irvin, maintain faith in Rieke-Smith’s leadership and the sometimes-slow road to change.

“I can’t honestly think of a person I would want more in this role at this time,” Irvin said. “Thanks to Dr. Sue, there have been a lot of changes that immediately took place after Hazelbrook.”

Dorsey, who also led the Education Equity Advisory Committee, was active in committees that helped craft the new strategic plan, and participated in annual budget planning, says he understands why the reaction time may appear slower to those who’ve missed incremental steps unfolding along the way.

“Dr. Sue is a role model for compassionate, transparent leadership,” he said, praising her commitment to fostering safe schools and quick response to incidents like Hazelbrook. “These things take time. It’s easy to finger-point. It’s not easy to fix.”