It’s a generations-old question in Oregon: Should people be allowed to take the water they need from the state’s rivers and streams if it comes at the expense of native fish species?

For decades, the law has tried to strike a balance when confronted with that question. But it’s always been something of a tightrope walk, especially as the state’s population has mushroomed in recent years and the demand for water along with it.

This is why Tigard City officials are closely watching a long-running legal challenge to Clackamas River water rights owned by Lake Oswego and several other agencies.

A legal challenge was initially undertaken back in 2008 by conservation group WaterWatch, which sought to limit the amount of water the Lake Oswego-Tigard Water Partnership and two other water districts could siphon from the river during times of low water flow. The lawsuit said that water rights to the Clackamas River held by the Partnership, the South Fork Water Board and the North Clackamas County Water Commission are a direct threat to native fish species that inhabit the river.

Now in 2021, after bouncing around several layers of the judicial system, that challenge is alive and well. The Oregon Court of Appeals in January heard arguments from both sides once again on the matter, and a decision is expected likely within the next six months. At issue is the amount of water cities, including Lake Oswego and Tigard, are allowed to draw from the river.

“It’s a problem all across Oregon,” said WaterWatch Executive Director John DeVoe. “The state has given away more rights on paper than it should have. And when these municipal rights spring up, they upset the apple cart and cause uncertainty for fish and for other users who may have more recent water rights.”

A 2014 decision from the Oregon Court of Appeals largely sided with WaterWatch and said the Oregon Water Resources Department (WRD) failed to explain how issuing permits to the Partnership and other agencies to draw water from the river “will maintain persistence of the listed fish species.” It ordered the WRD to reexamine the matter and come up with a better plan to protect native cutthroat trout, winter steelhead, spring and fall Chinook, and Coho salmon – the five species on the Clackamas River listed as protected by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

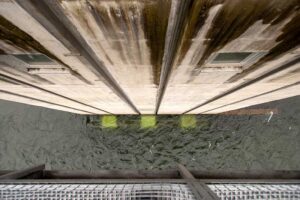

In the meantime, the Lake Oswego-Tigard Water Partnership in 2016 completed a $250 million infrastructure project to draw water from the Clackamas and supply it to users in both cities. That system recently celebrated its fifth anniversary.

WaterWatch filed another challenge against the WRD in 2016 seeking to overturn the final order the agency issued for Lake Oswego’s water rights. When that was unsuccessful, the group appealed to the Oregon Court of Appeals a second time.

The latest challenge was finally heard in January of this year by a three-judge panel. WaterWatch says that the WRD did not follow fish persistence rules because it did not consider all undeveloped water rights on the Clackamas River instead of just Lake Oswego’s.

“What we’d like to see is that the flows that the state has said are necessary to meet in the long term are met in the long term, and the permit conditions would be adequate to maintain these flows in the long term,” said Lisa Brown, an attorney for WaterWatch.

This could lead to limits on how much water Lake Oswego could pull from the river at certain times under certain conditions, she added.

“I think it’s important to say there’s a lot of water under different municipal permits in the metro area, and we do want to see cities meet their reasonable needs for water,” Brown said. “But we think there’s a way to do it without imperiling listed salmon and steelhead.”

Liz Newton, a Tigard City Councilor and a member of the Lake Oswego-Tigard Water Partnership Oversight Committee, said that even if the most recent court decision rules against Lake Oswego, any resulting cuts in the amount of water that could be taken from the Clackamas River should be manageable.

“We’re not talking about not being able to take any water from the river,” Newton said. “We’re talking about water use being curtailed, and we have a plan in place. If you have a dry summer, we have ASRs (aquifer storage and recovery wells) and we can ask people to conserve.”

She noted that the City’s participation in the separate Willamette Water Supply Program, which is intended to serve Hillsboro, Beaverton, Sherwood, Tigard and other westside cities in the future, is entirely unrelated to the legal issues surrounding Clackamas River water rights.

“It’s just the idea that Tigard is in a unique position to be able to avail itself of several options in order to make sure we’ve got them available,” Newton said, “We have options, and it just seems like the prudent thing to do.”