Children were important to early farming communities like Tigard because their labor contributed to their family’s well-being and prosperity. Children worked the farmlands, milked the cows, curried the horses, built the barns, picked the orchard fruit, flowers, onions, and hazelnuts, built the fences, collected firewood, dug ditches for irrigation, and planted and harvested crops. Most significantly, they inherited their parents’ land and passed on the family name. They attended East Butte School, built in 1896, and the Bend School on Bull Mountain, or the Durham Schoolhouse, built in 1920. They attended church with their parents on Sundays and often the socials held by the Grange, a political organization benefitting farmers. Children were greatly valued as life expectancy was shorter than in modern times.

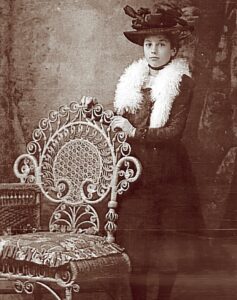

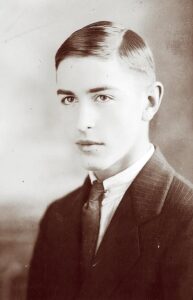

Families often had their pictures taken from a very young age to document their lives and preserve their memories. Early Tigardville (1886-1908) and then Tigard (1908-present) was a prosperous community, and farmers had elegant homes and the resources to document their lives with portraits. Children often rode their horses to school, where all grades shared a single classroom in the early days. There was a single stove and drinking cup shared by all. Older students often helped the younger students with their arithmetic and grammar. Teachers boarded around with the families of the school children, and their salary of $20 per month was paid by the community. Later the two-story East Butte School of 1896 held six rooms, and the students read from McGuffey’s Eclectic Reader and used the Spelling Book. The school that became the Charles F. Tigard School was built in 1922 on the site of the original 1853 log cabin school and was named for Charles F. Tigard, a son of the founder of Tigard, Wilson McClendon Tigard. The school girls wore white summer dresses for their graduation, which often doubled later as wedding dresses. Education was important to the children of early Tigard, and many went on to the Oregon Agricultural College (now OSU) for degrees in science and agriculture to benefit the business of farming.

In grade school, the children spoke a variety of languages, especially German, English, French, and Japanese, as early Tigard was a community of immigrants from many areas of the world. Children were locally hired to work in the stores such as the Tigardville General Store owned by Charles Fremont Tigard on Pacific Highway, or the Hugh Bulter Tigard Store on Main Street, where they could purchase a whole bag of candy for 5 cents. Often, youth worked in sawmills, grist mills, or flour mills in places like Oregon City. Curtis Tigard, a son of Charles F. Tigard, earned money by trapping and eradicating moles for farmers, and he enterprisingly sold their skins to Portland furriers. The children of the Tigard region intermarried, thus preserving their landholdings and business interests for heirs.

The history of childhood is a new field in social history that was catapulted to the forefront by Philippe Ariès Centuries of Childhood in 1960. This book explained that in ancient times children and youth were treated as adults writ small, but by the Enlightenment, children became separate beings considered in need of protection and guidance. John Locke, in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, explained the mind of a child as a tabula rasa or blank slate in need of education. Hence families taught their children moral ethics and prepared them for citizenship. Female children in Tigard were taught embroidery on samplers using Bible verses and the Golden Rule and learned spinning and carding wool, knitting, and lacemaking as well. Tigard children were taught the value of hard work, thrift, and charity. Children were carefully prepared for courtship, marriage, and parenthood, which ended their extended period of childhood. The Romantic period, which followed the Scientific Enlightenment, emphasized that children were pure and innocent, with painters like Joshua Reynolds painting pictures like The Age of Innocence c. 1785. This spirit carried over into the pastoral settlement of the West and the frontier, which celebrated the virtues of the yeoman farmer. The Industrial Revolution saw children working in factories but also protected them from hazards and exploitation with the Factory Acts or the Ten Hours Act. Americans sought to give their children every advantage starting with the benefits of compulsory education and the listing of childhood protections in legal statutes. High infant mortality in the 19th Century made children especially precious and endearing, as these Tigard pictures illustrate.

To become a member, volunteer, or for more information about the Tigard Historical Association visit www.tigardhistorical.org.