From hunting pheasants out of bedroom windows to witnessing the final atmospheric nuclear tests carried out by the U.S. government, Tigard resident Larry Jensen has lived a very interesting life.

Jensen has plenty of time to reflect on his experiences these days. He lives by himself in his childhood home at the corner of S.W. Tigard Street and 113th Place. There, he spends his evenings in a converted a garage that now serves as a home theater, complete with six stadium seats, a 106-inch display, surround sound, and a 3D projector.

It’s peaceful he says, and he wouldn’t trade it for anything.

“My parents bought this house and 2 acres of property with a great big two-story barn, cows, pigs, chickens, rabbits,” he said. “But it’s all changed.”

He’s approaching his 79th birthday and was born just as the United States entered World War II. He grew up in an era of post-war prosperity, back when Tigard had yet to be incorporated. He attended Tigard High School when it was located near what is now the Main Street McDonalds and Rite-Aid and was a part of the class of 1961. Only, he decided to enlist in the U.S. Navy along with a couple of friends before graduating.

“I had trouble reading and all that, and I had no interest in school,” Jensen said. “So, myself and two friends all quit and we joined the Navy.”

After basic training in San Diego, he was assigned to the USS Princeton, a World War II-era Essex class vessel that had just been converted into a helicopter carrier. Its crew was split evenly between the Navy and the U.S. Marine Corps.

“From there we went to Vietnam,” Jensen said.

It was April 1962, and the Princeton was assigned to deliver Marine Corps advisors and helicopters to Sóc Trăng in the Mekong Delta area of South Vietnam. Jensen was one of the ship’s photographer responsible for everything from candid shots of the crew carrying out responsibilities to aerial reconnaissance photography.

“I flew a lot,” he said. “We’d get in a helicopter and fly around and do different things. We delivered mail and stuff to Vietnam bases a couple of times.”

Jensen recalls that the Princeton took the first Army helicopters to Vietnam.

“The H-19s and H-21s, the big ol’ bananas, we took them to ‘Nam,” he said, “It was all exciting, but we were never around any combat or anything like that. We were a mixed crew, the photo lab was half Navy and half Marines. Our commanding officer, he got killed; they shot him down and he was killed, but that was the closest we came.”

Ironically, he was only sent to U.S. Navy Photo School in Pensacola, Florida, four years after he first enlisted. Prior to that, however, he and his Princeton shipmates had a front row seat to one of the most spectacular sights that humans have ever seen – even if it came with apocalyptic overtones.

From September to December 1962, the Princeton served as the flagship of Joint Task Force 8 as they took part in Operation Dominic – a series of 36 nuclear weapons tests around Johnston Island in the South Pacific Ocean.

“We got to observe five or six atomic bomb blasts and we were exposed to ionizing radiation,” Jensen said. “And that’s probably why I have 100 percent disability now, because of that. It was so exciting, though, we were probably 30 to 40 miles away. But we were close enough to feel the heat and the blast waves from them.”

Some of these were missile shots, he added, including the largest outer space explosion ever achieved, a shot called Starfish Prime. The blast was measured at 1.4 megatons and was carried out when a Thor missile lofted a W49 warhead roughly 250 miles into space.

“That was a beautiful thing, it was gorgeous,” Jensen said. “The colors were fascinating, it was all pastels, pastel greens and oranges and reds. It knocked out the power in Honolulu; it was the first time they experienced EMP. That’s one reason I’m so prepared now. I’m a survivalist now, a prepper.”

Despite the exposure to radiation, the closest Jensen ever came to death during his time in the service was when a camera battery pack for his Arriflex 16mm movie camera fell to the floor of the F-4 Phantom he happened to be riding in. The battery pack lodged the backseat control stick in place as the plane was in a gentle dive. Jensen and his pilot were seconds from ejecting when he managed to pry the battery pack free, allowing the pilot to regain control.

“We were headed for the ground and I felt that thing with my foot somehow and pushed it out of the way,” Jensen said. “And he said, ‘Hang on, don’t eject, I’ve got control back.’ And I was up here with my hands on the handles ready to go, ready to pull down the curtain and eject.”

Larry Jensen (right) on the flight deck of the USS Princeton at sea.

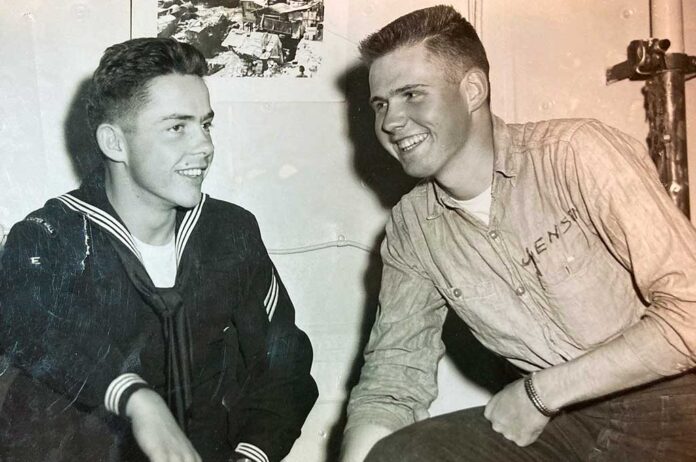

Larry Jensen (right) is shown with a shipmate inside the dry dock in Long Beach where the USS Princeton was scheduled to undergo modification from a traditional aircraft carrier to helicopter carrier.

The five photographers of the USS Princeton’s photo crew pose for a group shot. Larry Jensen is at bottom left.

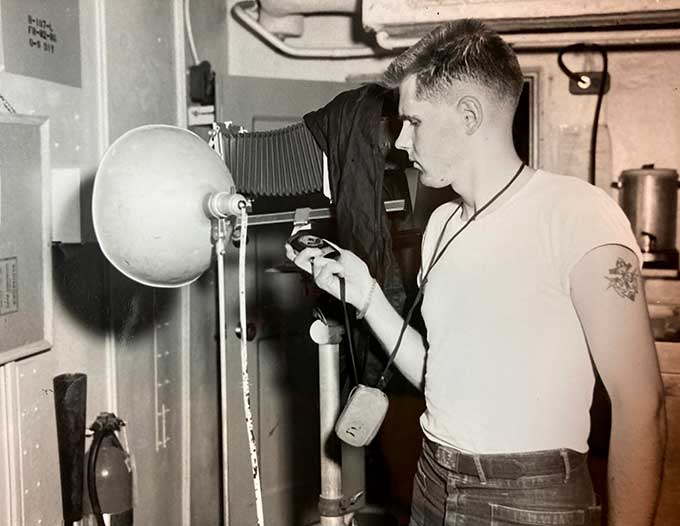

Larry Jensen is shown here making copies of prints in the Princeton’s photo lab.

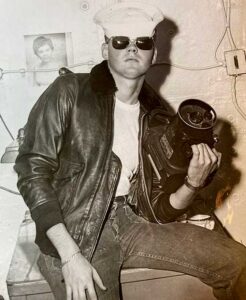

Larry Jensen holds up one of the five cameras he will take with him on a photo reconnaissance flight.

Larry Jensen (front row, middle) takes part in a Petty Officer promotion ceremony aboard the Princeton.