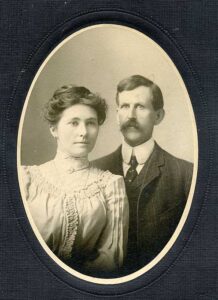

As a sixth-generation Oregonian and professional historian, I am passionate about studying the diverse people that make up our shared past. Recently, I came across a portrait of the first doctor in Tigard, Sylvester Ruel Vincent and his second wife, Elizabeth Hohman Grove Vincent taken circa 1905. The image was not unique, but the caption provided names and his occupation, which is rare with old photos. Driven by curiosity, I set out to discover more using ancestry, newspapers and local history. Fortunately, Mary Payne had written a chapter on the Vincent family in Tigardville-Tigard published in 1979. Her research was largely accurate, so I looked beyond the established timeline to uncover some context about their personal experiences.

Sylvestor Ruel Vincent was born in 1862 to a Michigan family of nine children and his parents ensured that all were educated as teachers and doctors, except the youngest son who inherited the family farm. Sylvester married Tillie Preston and they had two sons, George and Arthur, but sadly their mother passed of an unknown cause in 1899. Hopefully the doctor did not blame himself for her death, but he remained a single father until marrying Elizabeth Hohman Grove in 1905.

Even though Elizabeth has been recorded as a “childless widow” and sister of Mrs. Rosa Tigard, she should be remembered as a dedicated step-mother and homemaker, fervent Evangelical church-goer and member of the Tigard Grange for forty-four years. The newly formed family settled on the corner of 102nd and McDonald Street and Dr. Vincent bought a 1911 Maxwell automobile to make home visits faster when roads were passable.

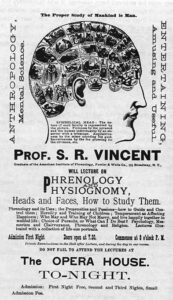

In the late 1880s, he graduated from the American Institute of Phrenology, a now extinct school of thought proven to be blatantly racist and empirically unsound. Doctors attempted to determine the virtues of a person according to the size, shape and geography of the skull, playing into that terrible system in which whites were considered superior to minorities. Dr. Vincent “travelled and lectured” on the subject for several years, providing complicated charts, charismatic speeches and private examinations.

It is unknown if he kept practicing that quackery, but Sylvestor and his brother Arthur travelled together to Chicago in 1893 to attend the newly formed Hering Medical College of Homeopathy. An offshoot and competitor to another school, professors taught that a body could cure itself through a “single remedy, potentized.” Rather than traditional homeopathy encouraging diluted doses over time, the Vincent’s learned to administer one large, concentrated dose of drugs. In other words, if the doctor did not kill the patient first, they would be totally cured.

General homeopathy was widely accepted in the United States by the turn of the twentieth century, but there were many versions, from beneficial midwifery to the dangerous methods above. Eventually, the 1909 Flexner Report condemned most homeopathic schools, instead supporting safe, reputable scientific institutions. Despite any criticism about practice, both Sylvester and Arthur Vincent had already secured positions locally and continued adapting to fast-paced scientific change. S.R. Vincent lived in Tigard and practiced on Boones Ferry Road at Tualatin-Sherwood, while his brother posted to St. Johns.

Dr. Arthur W. Vincent also married, becoming physician and mayor of his town on a controversial Socialist platform. He and his wife Hannah lost their eldest son Byron in 1905 at only fifteen years old. One evening in 1910, Arthur went to tend the poor child’s grave at Fairview and a suspicious patron thought he was depositing the body of a missing woman. The St. Johns Review recounted that the witness admitted their mistake after Arthur explained to authorities that he was only repairing damage caused by a recent nearby burial.

The Vincent brothers and their families tootled around the Oregon countryside for one summer in their new motor carriages. On one extraordinary trip to Mount Hood in June 1911, the two families camped at the foot of the rocky giant near Sandy. Arthur, his younger son Chester, two nephews and a Miss Fassett all hiked up to Crater Rock summit! The ambitious group accomplished the climb with no trails, lifts, or lodges and were limited to Edwardian-era hiking gear.

Only a year after Sylvester Vincent acquired his 1911 Maxwell, he was hit by the Oregon Electric train at the Tigard stop on the way to see a patient. Accounts say he couldn’t hear the iron beast as it slowed to stop. The doctor was thrown and the car destroyed, but he survived a serious head wound and went back to work. Mary Payne said that “internal injuries” caught up with him in 1918 though, and he was buried at Crescent Grove. Likely devastated, Elizabeth continued raising the two boys and participating in the community, until joining him at the cemetery in 1951.